- Delboeuf Illusion And Foods

- Delboeuf Illusion And Food And Drink

- Delboeuf Illusion And Food Industry

- Delboeuf Illusion And Food Truck

The Delboeuf illusion (often in connection with the Ebbinghaus illusion) has been used with great frequency in testing animal perception, since the ability to discern size seems highly relevant for many aspects of survival, particularly regarding food. The perception of the Delboeuf illusion differs greatly depending on the species. The Delboeuf illusion appears within real-world decisional settings as well, such that adult humans overestimate food portions (e.g., amounts of cereal) presented in small dishware (assimilation. Jun 07, 2018 Use the Delboeuf Illusion to influence elderly food consumption? If you are not familiar, the Delboeuf illusion is an optical illusion of relative size perception. The best-known image exemplifying this illusion is two circles of identical size placed near to each other. One is surrounded with another circle. Sep 12, 2019 The idea is based on something called the Delboeuf Illusion, which claims that using a smaller plate will not only help to serve less food, but the portion will actually appear larger and more filling. Torrent downloader mac 64 bit. In turn, you will feel like you’ve eaten a lot while actually eating less.

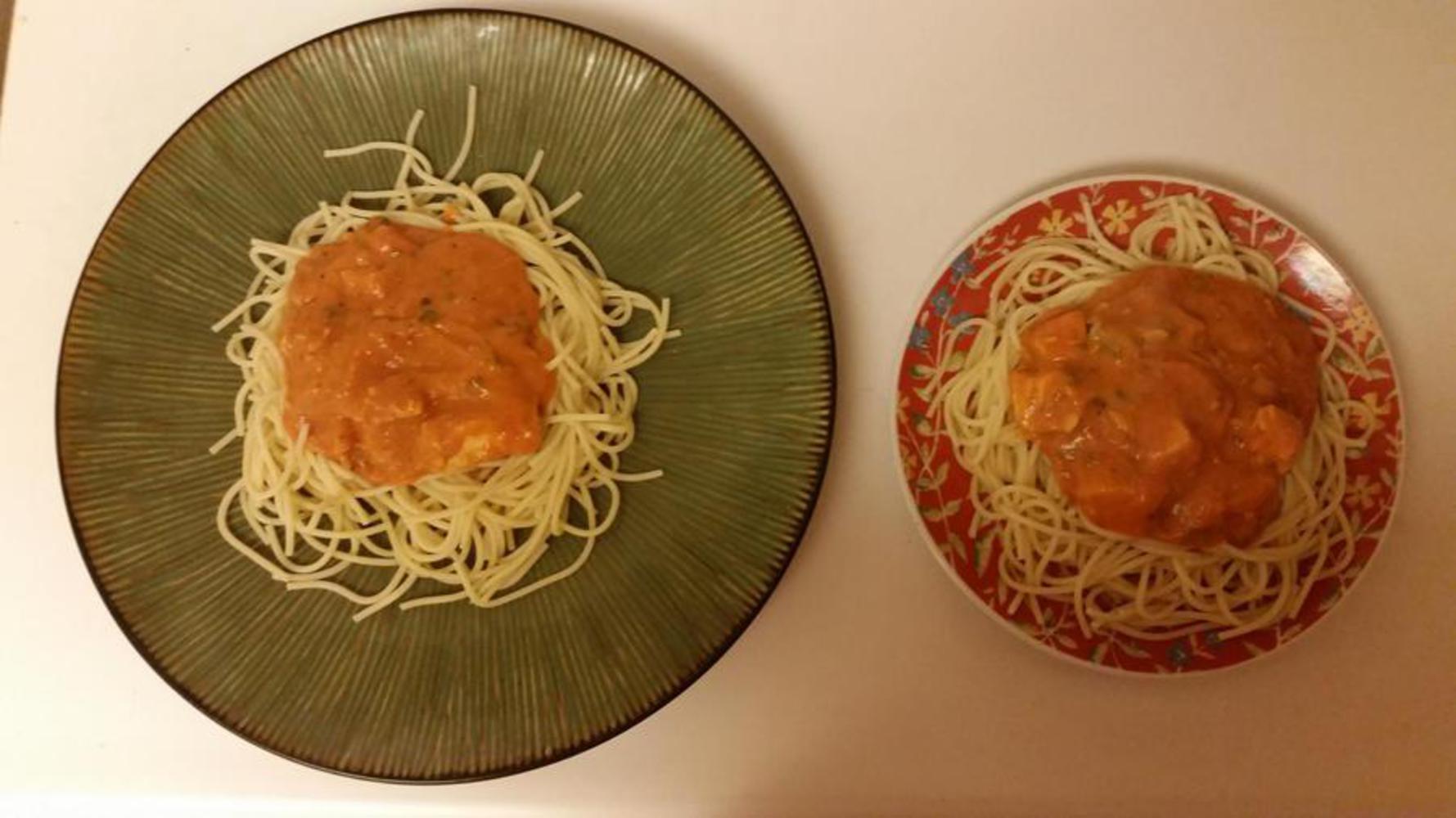

You might not know how much food is on your plate. That's okay. Neither do I. That’s because it depends on the plate.

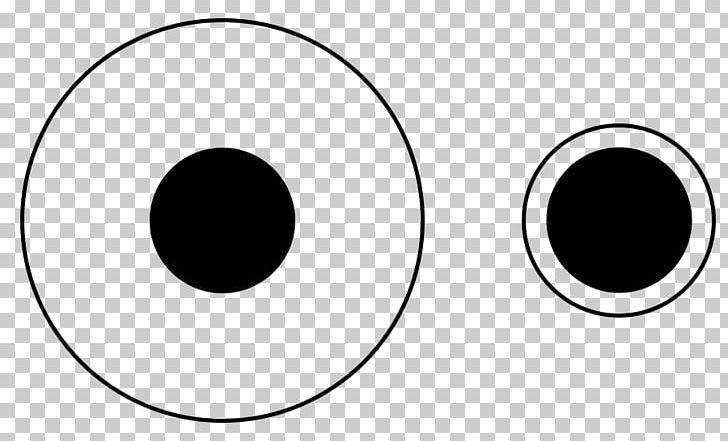

See. The inner black circle on the left appears larger than the black circle on the right, but both black circles are actually the same size.

Meet the Delboeuf illusion, where we misperceive the size of a central circle because of what’s surrounding it. In the image above, the black circle on the left is surrounded by a smaller circle, giving it the appearance that it’s larger than the black circle on the right, which is surrounded by a larger circle.

Which brings us back to plates of food. It is the Delboeuf illusion that tricks us into thinking we have more food when it is on a smaller plate. That is why a search for the Delboeuf illusion on the Internet produces hits for weight loss this and weight loss that. Select the right plate, you are told, and you could consume less food. (I write that while eating frosting with a spoon. Am I even qualified to cover this topic? I digress.)

Visual illusions are not just for humans. Male bowerbirds not only construct elaborately decorated structures (bowers) to attract mates, they do so in a way that creates the illusion that they are bigger, thus potentially increasing mating success. Felicity Muth of Not Bad Science explains that if a sneaky researcher moves objects within a bird’s bower and disrupts the illusion, males will reposition the objects to fix the disturbed illusion. Don’t mess with my stuff.Bowerbirds are not alone. Mongodb docker install. Numerous other animals also use, and are fooled by, visual trickery.

But it is not always easy to tell if another species picks up on illusions. In recent years, researchers turned to different methods to find out, such as the ‘spontaneous preference paradigm.’ Here’s how it works: Step 1: in control trials, determine whether animals spontaneously select the larger quantity of food when presented with two options. If they do, great. That sets a precedent for the next part. Step 2: in test trials, present them with food on plates in such a way that implements the Delboeuf illusion—the same amount of food is on each plate, but the plates differ in size. Those who initially went for more food would reveal themselves as susceptible to the illusion if they then select the smaller plate—the one that, according to the Delboeuf illusion, appears to have more food on it. Using this design, Parrish and Beran (2014) found that three chimpanzees fell for it, selecting the larger portion in control trials and then selecting food on the smaller plate in test trials. More recently, capuchin monkeys and rhesus monkeys were found to be generally fooled by the illusion.

What about the hounds? Bring in the hounds. Researchers from the University of Padua in Italy recently investigated the Delboeuf illusion in dogs. A total of thirteen dogs, both pet dogs and those residing at an animal shelter, participated in the study by Maria Elena Miletto Tetrazzini and colleagues, which appeared online this month in Animal Cognition. The dog study was modeled after Parrish and Beran’s 2014 study with chimpanzees, first determining whether the dogs preferred larger quantities of food and then presenting equal amounts of food on two different-size plates.

Delboeuf Illusion And Foods

Like the chimpanzees, dogs preferred more food, but unlike the chimps, when dogs were presented with equal amounts of food on different-size plates, dogs did not show a preference for the smaller plate. They went to either plate. The Delboeuf illusion, it appears, is not for dogs.

If bells are going off in your head, let me guess: are you wondering about smell? In the control trials, did the dogs go to the plate with more food because they smelled the difference in quantity? On the other hand, in the test trials could dogs smell that the quantities were the same, so plate-schmate, it’s all the same?

Delboeuf Illusion And Food And Drink

A number of studies, including one I participated in, find something surprising: “Dogs’ ability to discriminate between two quantities of food items by using olfactory cues is surprisingly poor,” summarizes Miletto Petrazzini.

No one, of course, is suggesting that dogs can’t use olfactory information to discriminate between amounts. Around the globe, trained dogs show off this ability daily. Instead, the studies suggests that average, untrained dogs are not necessarily attending to minute differences in olfactory cues. Additionally, in the Delboeuf test, the plates were about 5 feet from the dogs. Close olfactory investigation and comparison prior to making a decision, like in this video, was not possible.

The Delbouef story does not end here. A second study, also online this month in Animal Cognition, investigated the Delboeuf illusion with an entirely different procedure and also concluded that most dogs do not pick up on it. Here, Sarah-Elizabeth Byosiere and colleagues at La Trobe University in Australia first used a positive reinforcement protocol to train eight dogs—in this case all Lagotto Romagnolos—to discriminate large from small circles presented on a computer screen. Then, dogs were tested on their susceptibility to different visual illusions. Again, Delboeuf was not in the cards for most dogs, although the two dogs who did pick up on it did so in the opposite direction as humans; in other words, the inner circle that appears larger to humans appeared smaller to dogs, and the inner circle that looks smaller to humans looked larger to dogs.

Visual illusions are not just for humans. Male bowerbirds not only construct elaborately decorated structures (bowers) to attract mates, they do so in a way that creates the illusion that they are bigger, thus potentially increasing mating success. Felicity Muth of Not Bad Science explains that if a sneaky researcher moves objects within a bird’s bower and disrupts the illusion, males will reposition the objects to fix the disturbed illusion. Don’t mess with my stuff.Bowerbirds are not alone. Mongodb docker install. Numerous other animals also use, and are fooled by, visual trickery.

But it is not always easy to tell if another species picks up on illusions. In recent years, researchers turned to different methods to find out, such as the ‘spontaneous preference paradigm.’ Here’s how it works: Step 1: in control trials, determine whether animals spontaneously select the larger quantity of food when presented with two options. If they do, great. That sets a precedent for the next part. Step 2: in test trials, present them with food on plates in such a way that implements the Delboeuf illusion—the same amount of food is on each plate, but the plates differ in size. Those who initially went for more food would reveal themselves as susceptible to the illusion if they then select the smaller plate—the one that, according to the Delboeuf illusion, appears to have more food on it. Using this design, Parrish and Beran (2014) found that three chimpanzees fell for it, selecting the larger portion in control trials and then selecting food on the smaller plate in test trials. More recently, capuchin monkeys and rhesus monkeys were found to be generally fooled by the illusion.

What about the hounds? Bring in the hounds. Researchers from the University of Padua in Italy recently investigated the Delboeuf illusion in dogs. A total of thirteen dogs, both pet dogs and those residing at an animal shelter, participated in the study by Maria Elena Miletto Tetrazzini and colleagues, which appeared online this month in Animal Cognition. The dog study was modeled after Parrish and Beran’s 2014 study with chimpanzees, first determining whether the dogs preferred larger quantities of food and then presenting equal amounts of food on two different-size plates.

Delboeuf Illusion And Foods

Like the chimpanzees, dogs preferred more food, but unlike the chimps, when dogs were presented with equal amounts of food on different-size plates, dogs did not show a preference for the smaller plate. They went to either plate. The Delboeuf illusion, it appears, is not for dogs.

If bells are going off in your head, let me guess: are you wondering about smell? In the control trials, did the dogs go to the plate with more food because they smelled the difference in quantity? On the other hand, in the test trials could dogs smell that the quantities were the same, so plate-schmate, it’s all the same?

Delboeuf Illusion And Food And Drink

A number of studies, including one I participated in, find something surprising: “Dogs’ ability to discriminate between two quantities of food items by using olfactory cues is surprisingly poor,” summarizes Miletto Petrazzini.

No one, of course, is suggesting that dogs can’t use olfactory information to discriminate between amounts. Around the globe, trained dogs show off this ability daily. Instead, the studies suggests that average, untrained dogs are not necessarily attending to minute differences in olfactory cues. Additionally, in the Delboeuf test, the plates were about 5 feet from the dogs. Close olfactory investigation and comparison prior to making a decision, like in this video, was not possible.

The Delbouef story does not end here. A second study, also online this month in Animal Cognition, investigated the Delboeuf illusion with an entirely different procedure and also concluded that most dogs do not pick up on it. Here, Sarah-Elizabeth Byosiere and colleagues at La Trobe University in Australia first used a positive reinforcement protocol to train eight dogs—in this case all Lagotto Romagnolos—to discriminate large from small circles presented on a computer screen. Then, dogs were tested on their susceptibility to different visual illusions. Again, Delboeuf was not in the cards for most dogs, although the two dogs who did pick up on it did so in the opposite direction as humans; in other words, the inner circle that appears larger to humans appeared smaller to dogs, and the inner circle that looks smaller to humans looked larger to dogs.

Nowadays, studies and news reports often highlight the similarities between dogs and people, as if we are two peas in a pod. 'Dogs do it like we do,' reports seem to say. 'We're on the same page.' But upon closer inspection, dogs often reveal their own dog-like way of processing and attending to the world. Understanding our differences, I’d argue, only strengthens our collective pod.

References

Applications of the Delbouef Illusion

Which circle below looks bigger?

Delboeuf Illusion And Food Industry

Having already learned about the Ebbinghaus illusion, you were probably right in guessing that the circle with the ring around it appears larger than the non-surrounded circle. This is an example of the Delboeuf illusion, first identified by Belgian philosopher and mathematician Joseph Delbouef in 1887 or 1888. Modern psychologists have tested this illusion in various experiments, including one to determine if eyeshadow makes eyes look bigger (it does), and others to determine if the quantity of food on a plate looks larger if the plate is smaller.

Delboeuf Illusion And Food Truck

Studies by Koert Van Ittersum and Brian Wansink[1] at the Cornell Food and Brand Lab have studied the effect of the Delbouef illusion on eating and serving behavior. In several different experiments, they measured if people would take more or less than a typical serving size depending on the size of their plate, the color of the plate, the color of the tablecloth, and how much they knew about the Delboeuf illusion.